CHAPTER VI.

Pg. 78

- Freeman's Industry

- Cleanliness and Clothes

- Exercising in the Show Room

- The Dance

- Bob, the Fiddler

- Arrival of Customers

- Slaves Examined

- The Old Gentleman of New-Orleans

- Sale of David, Caroline, and Lethe

- Parting of Randall and Eliza

- Small Pos

- The Hospital

- Recovery and Return to Freeman's Slave Pen

- The Purchaser of Eliza, Harry, and Platt

- Eliza's Agony on Parting from Little Emily

THE

very amiable, pious-hearted Mr. Theophilus

Freeman, partner or consignee of James H.

Burch, and keeper of the slave pen in

New-Orleans, was out among his animals early in the

morning. With an occasional kick of the older

men and women, and many a sharp crack of the whip

about the ears of younger slaves, it was not long

before they were all astir, and wide awake.

Mr. Theophilus Freeman bustled about in a very

industrious manner, getting his property ready for

the sales room, intending, no doubt, to do that day

a rousing business.

In the first place we were required to wash thoroughly,

and those with beards, to shave. We were then

furnished with a new suit each, cheap, but clean.

The men had hat, coat, shirt, pants and shoes; the

women frocks of calico, and handkerchiefs to bind

about their heads. We were now conducted into

a large room in the front part of the building to

which

[pg. 79]

the yard was attached, in order to

be properly trained, before the admission of

customers. The men were arranged on one side

of the room, the women on the other. The

tallest was placed at the head of the row, then the

next tallest, and so on in the order of their

respective heights. Emily was at the

foot of the line of women. Freeman

charged us to remember our places; exhorted us to

appear smart and lively, - sometimes threatening,

and again, holding out various inducements.

During the day he exercised us in the art of

"looking smart," and of moving to our places with

exact precision.

After being fed, in the afternoon, we were again

paraded and made to dance. Bob, a

colored boy, who had some time belonged to

Freeman, played on the violin. Standing

near him, I made bold to inquire if he could play

the "Virginia Reel." He answered he could not,

and asked me if I could play. Replying in the

affirmative, he handed me the violin. I struck

up a tune, and finished it. Freeman

ordered me to continue playing, and seemed well

pleased, telling Bob that I far excelled him

- a remark that seemed to grieve my musical

companion very much.

Next day many customers called to examine Freeman's

"new lot." The latter gentleman was very

loquacious, dwelling at much length upon our several

good points and qualities. He would make us

hold up our heads, walk briskly back and forth,

while customers would feel of our hands and arms and

bodies, turn us about, ask us what we could do, make

us open

[pg. 80]

our mouths and show our teeth,

precisely as a jockey examines a horse which he is

about to barter for or purchase. Sometimes a

man or woman was taken back to the small house in

the yard, stripped, and inspected more minutely.

Scars upon a slave's back were considered evidence

of a rebellious or unruly spirit and hurt his sale.

One old gentleman, who said he wanted a coachman,

appeared to take a fancy to me. From his

conversation with Freeman, I learned he was a

resident in the city. I very much desired that

he would buy me, because I conceived it would not be

difficult to make my escape from New-Orleans on some

northern vessel. Freeman asked him

fifteen hundred dollars for me. The old

gentleman insisted it was too much, as times were

very hard. Freeman, however, declared

that I was sound and healthy, or a good

constitution, and intelligent. He made it a

point to enlarge upon my musical attainments.

The old gentleman argued quite adroitly that there

was nothing extraordinary about the nigger, and

finally, to my regret, went out, saying he would

call again. During the day, however, a number

of sales were made. David and Caroline

were purchased together by a Natchez planter.

They left us, grinning broadly, and in the most

happy state of mind, caused by the fact of their not

being separated. Lethe was sold to a

planter of Baton Rouge, her eyes flashing with anger

as she was led away.

The same man also purchased Randall. The

little fellow was made to jump, and run across the

floor,

[pg. 81]

and perform many other feats,

exhibiting his activity and condition. All the

time the trade was going on, Eliza was crying

aloud, and wringing her hands. She besought

the man not to buy him, unless he also bought

herself and Emily. She promised, in

that case, to be the most faithful slave that ever

lived. The man answered that he could not

afford it, and then Eliza burst into a

paroxysm of grief, weeping plaintively.

Freeman turned round to her, savagely, with his

whip in his uplifted hand, ordering her to stop her

noise, or he would flog her. He would not have

such work - such sniveling; and unless she ceased

that minute, he would take her to the yard and give

her a hundred lashes. Yes, he would take the

nonsense out of her pretty quick - if he didn't,

might he be d__d. Eliza shrunk before

him, and tried to wipe away her tears, but it was

all in vain. She wanted to be with her

children, she said, the little time she had to live.

All the frowns and threats of Freeman, could

not wholly silence the afflicted mother. She

kept on begging and beseeching them, most piteously,

not to separate the three. Over and over again

she told them how she loved her boy. A great

many times she repeated her former promises - how

very faithful and obedient she would be; how hard

she would labor day and night, to the last moment of

her life, if he would only buy them all together.

But it was of no avail; the man could not afford it.

The bargain was agreed upon, and Randall must

go alone. Then Eliza ran to him;

embraced him passionately; kissed

[pg. 82]

him again and again; told him to

remember her - all the while her tears falling in

the boy's face like rain.

Freeman damned her, calling her a blubbering,

bawling wench, and ordered her to go to her place,

and behave herself, and be somebody. HE swore

he wouldn't stand such stuff but a little longer.

He would soon give her something to cry about, if

she was not mighty careful, and that she

might depend upon.

The planter from Baton Rouge, with his new purchases,

was ready to depart.

"Don't cry, mama. I will be a good boy.

Don't cry," said Randall, looking back, as

they passed out of the door.

What has become of the lad, God knows. It was

mournful scene indeed. I would have cried

myself if I had dared.

That night, nearly all who came in on the brig Orleans,

were taken ill. They complained of violent

pain in the head and back. Little Emily

- a thing unusual with her - cried constantly.

In the morning a physician was called in, but

was unable to determine the nature of our complaint.

while examining me, and asking questions touching my

symptoms, I gave it as my opinion that it was an

attack of smallpox - mentioning the fact of

Robert's death as the reason of my belief.

It might be so indeed, he thought, and he would send

for the head physician of the hospital.

Shortly, the head physician came - a small,

light-haired man, whom they called Cr. Carr.

He

[pg. 83]

pronounced it small-pox, whereupon

there was much alarm throughout the yard. Soon

after Dr. Carr left, Eliza, Emmy, Harry

and myself were put into a hack and driven to

the hospital - a large white marble building,

standing on the outskirts of the city.

Henry and I were placed in a room in one of the

upper stories. I became very sick. For

three days I was entirely blind. While lying

in this state one day, Bob came in, saying to

Dr. Carr that Freeman had sent him over

to inquire how we were getting on. Tell him,

said the doctor, that Piatt is very bad, but

that if he survives until nine-o'clock, he may

recover.

I expected to die.

Though there was little in the prospect before me

worth living for, the near approach of death

appalled me. I thought I could have been

resigned to yield up my life in the bosom of my

family, but to expire in the midst of strangers,

under such circumstances, was a bitter reflection.

There were a great

number in the hospital, of both sexes, and of all

ages. In the rear of the building coffins were

manufactured. When one died, the bell tolled -

a signal to the undertaker to come and bear away the

body to the potter's field. Many times, each

day and night, the tolling bell sent forth its

melancholy voice, announcing another death.

But my time had not yet come. The crisis

having passed, I began to revive, and at the end of

two weeks and two days, returned with Harry

to the pen, bearing upon my face the effects of the

malady, which to this day continues to disfigure it.

Eliza and Emily were also

[pg. 84]

brought back next day in a hack, and

again were we paraded in the sales-room, for the

inspection and examination of purchasers. I

still indulged the hop that the old gentleman in

search of a coachman would call again, as he had

promised, and purchase me. In that event I

felt an abiding confidence that I would soon regain

my liberty. Customer after customer entered,

but the old gentleman never made his appearance.

At length, one day, while we were in the yard,

Freeman came out and ordered us to our places,

in the great room. A gentleman was waiting for

us as we entered, and inasmuch as he will be often

mentioned in the progress of this narrative, a

description of his personal appearance, and my

estimation of his character, at first sight, may not

be out of place.

He was a man above the ordinary height, somewhat bent

and stooping forward. He was a good-looking

man, and appeared to have reached about the middle

age of life. There was nothing repulsive in

his presence; but on the other land, there was

something cheerful and attractive in his face, and

in his tone of voice. The finer elements were

all kindly mingled in his breast, as any one could

see. He moved about among us, asking many

questions, as to what we could do, and what labor we

had been accustomed to; if we thought we would like

to live with him, and would be good boys if he would

buy us, and other interrogatories of life character.

After some further inspection, and conversation

[pg. 85]

touching prices, he finally offered

Freeman one thousand dollars for me, nine

hundred for Harry, and seven hundred for

Eliza. Whether the small-pox had

depreciated our value, or from what cause Freeman

had concluded to fall five hundred dollars from the

price I was before held at, I cannot say. At

any rate, after a little shrewd reflection, he

announced his acceptance of the offer.

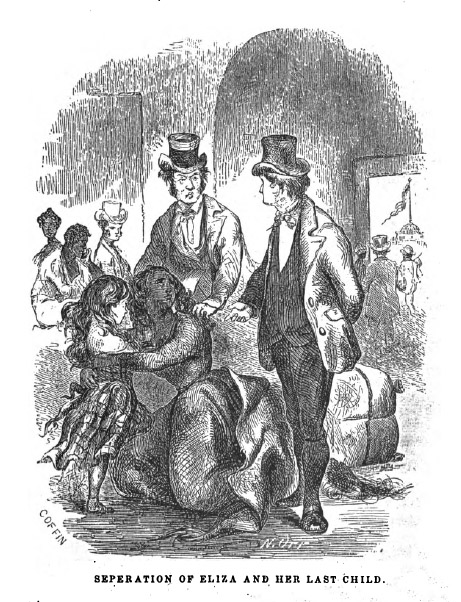

As soon as Eliza heard it, she was in an agony

again. By this time she had become haggard and

hollow-eyed with sickness and with sorrow. It

would be a relief if I could consistently pass over

in silence the scene that now ensued. It

recalls memories more mournful and affecting that

any language can portray. I have seen mother's

kissing for the last time the faces of their dead

offspring. I have seen them looking down into

the grave, as the earth fell with a dull sound upon

their coffins, hiding them from their eyes forever;

but never have I seen such an exhibition of intense,

unmeasured, and unbounded grief, as when Eliza

was parted from her child. She broke from

her place in the line of women, and rushing down

where Emily was standing, caught her in her

arms. The child, sensible of some impending

danger, instinctively fastened her hands around her

mother's neck, and nestled her little head upon her

bosom. Freeman sternly ordered her to

be quiet, but she did not heed him. He caught

her by the arm and pulled her rudely, but she only

clung the closer to the child. Then, with a

volley of great oaths, he struck her such

[pg. 86]

a heartless blow, that she staggered

backward, and was like to fall. Oh! how

piteously then did she beseech and beg and pray that

they might not be separated. Why could they

not be purchased together? Why not let her

have one of her dear children? "Mercy, mercy,

master!" she cried, falling on her knees.

"Please, master, buy Emily. I can never

work any if she is taken from me: I will die."

Freeman interfered again, but, disregarding him,

she still plead most earnestly, telling how

Randall had been taken from her - how she never

would see him again, and now it was too bad - oh,

God! it was too bad, too cruel, to take her

away from Emily - her pride - her only

darling, that could not live, it was so young,

without its mother!

Finally, after much more of supplication, the purchaser

of Eliza stepped forward, evidently affected,

and said to Freeman he would buy Emily,

and asked him what her price was.

"What is her price? Buy her? was the

responsive interrogatory of Theophilus Freeman.

And instantly answering his own inquiry, he added,

"I won't sell her. She's not for sale.

The man remarked he was not in need of one so young -

that it would be of no profit to him, but since the

mother was so fond of her, rather than see them

separated, he would pay a reasonable price.

But to this humane proposal Freeman was

entirely deaf. He would not sell her then on

any account whatever. There were heaps and

piles of money to

[pg. 87]

be made of her, he said, when she

was a few years older. There were men enough

in New-Orleans who would give five thousand dollars

for such an extra, handsome, fancy piece as Emily

would be, rather than not get her. No, no, he

would not sell her then. She was a beauty - a

picture - a doll - one of the regular bloods - none

of your thick-lipped, bullet headed, cotton-picking

niggers - if she was might he be d--d.

When Eliza heard Freeman's determination

not to part with Emily, she became absolutely

frantic.

"I will not go without her. They shall

not take her from me," she fairly

shrieked, her shrieks commingling with the loud and

angry voice of Freeman, commanding her to be

silent.

Meantime Harry and myself had been to the yard

and returned with our blankets, and were at the

front door ready to leave. Our purchaser stood

near us, gazing at Eliza with an expression

indicative of regret at having bought her at the

expense of so much sorrow. We waited some

time, when, finally, Freeman, out of

patience, tore Emily from her mother by main

force, the two clinging to each other with all their

might.

"Don't leave me, mama - don't leave me," screamed

the child as its mother was pushed harshly forward;

"Don't leave me - come back, mama," she still cried,

stretching forth her little arms imploringly.

But she cried in vain. Out of the door and

into the street we were quickly hurried. Still

we could hear

[pg. 88]

her calling to her mother, "Come

back - don't leave me - come back, mama," until her

infant voice grew faint and still more faint, and

gradually died away, as distance intervened, and

finally was wholly lost.

Eliza never after saw or heard of Emily

or Randall. Day nor night, however,

were they ever absent from her memory. In the

cotton field, in the cabin, always and everywhere,

she was talking of them - often to them, as

if they were actually present. Only when

absorbed in that illusion, or asleep, did she ever

have a moment's comfort afterwards.

She was no common slave, as has been said. To a

large share of natural intelligence which she

possessed, was added a general knowledge and

information on most subjects. She had enjoyed

opportunities such as are afforded to very few of

her oppressed class. She had been lifted up

into the regions of a higher life. Freedom -

freedom for herself and for her offspring, for many

years had been her cloud by day, her pillar of fire

by night. In her pilgrimage through the

wilderness of bondage, with eyes fixed upon that

hope inspiring beacon, she had at length ascended to

"the top of Pisgah," and beheld "the land of

promise." In an unexpected moment she was

utterly overwhelmed with disappointment and despair.

The glorious vision of liberty faded from her sight

as they led her away into captivity. Now "she

weepeth sore in the night, and tears are on her

cheeks: all her friends have dealt treacherously

with her: they have become her enemies.

<

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS >