|

STILL'S

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORDS,

REVISED EDITION.

(Previously Published in 1879 with title: The Underground Railroad)

WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

NARRATING

THE HARDSHIPS, HAIRBREADTH ESCAPES AND DEATH STRUGGLES

OF THE

SLAVES

IN THEIR EFFORTS FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WITH

SKETCHES OF SOME OF THE EMINENT FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, AND

MOST LIBERAL AIDERS AND ADVISERS OF THE ROAD

BY

WILLIAM STILL,

For many years connected with the Anti-Slavery Office in

Philadelphia, and Chairman of the Acting

Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground

Rail Road.

Illustrated with 70 Fine Engravings

by Bensell, Schell and Others,

and Portraits from Photographs from Life.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his

master the servant that has escaped from his master unto thee. -

Deut. xxiii 16.

SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM STILL, PUBLISHER

244 SOUTH TWELFTH STREET.

1886

pp. 277 - 314

[Pg. 277]

THE PROTECTION OF SLAVE PROPERTY IN VIRGINIA.

A BILL PROVIDING ADDITIONAL PROTECTION FOR THE SLAVE

PROPERTY OF CITIZENS OF THIS COMMONWEALTH.

(1.) Be it enacted, by

the General Assembly, that it shall not be lawful for

any vessel, of any size or description, whatever, owned

in whole, or in part, by any citizen or resident of

another State, and about to sail or steam for any port

or place in this State, for any port or place north of

and beyond the capes of Virginia, to depart from the

waters of this commonwealth, until said vessel has

undergone the inspection hereinafter provided for in

this act, and received a certificate to that effect.

If any such vessel shall depart from the State without

such certificate of inspection, the captain or owner

thereof, shall forfeit and pay the sum of five hundred

dollars, to be recovered by any person who will sue for

the same, in any court of record in this State, in the

name of the Governor of the Commonwealth.

[Pg. 278]

Pending said suit, the vessel of said captain or owner

shall not leave the State until bond be given by the

captain or owner, or other person for him, payable to

the Governor, with two or three sureties satisfactory to

the court, in the penalty of one thousand dollars, for

the payment of the forfeit or fine, together with the

cost and expenses incurred in enforcing the same; and in

default of such bond, the vessel shall be held liable.

Provided that nothing contained in this section, shall

apply to vessels belonging to the United States

Government, or vessels, American or foreign, bound

direct to any foreign country other than the British

American Provinces.

(2.) The pilots licensed under the laws of Virginia,

and while attached to a vessel regularly employed as a

pilot boat, are hereby constituted inspectors to execute

this act, so far as the same may be applicable to the

Chesapeake Bay, and the waters tributary thereto, within

the jurisdiction of this State, together with such other

inspectors as may be appointed by virtue of this act.

(3.) The branch or license issued to a pilot according

to the provisions of the 92d chapter of Code, shall be

sufficient evidence that he is authorized and empowered

to act as inspector as aforesaid.

(4.) It shall be the duty of, the inspector, or other

person authorized to act under this law, to examine and

search all vessels hereinbefore described, to see that

no slave or person held to service or labor in this

State, or person charged with the commission of any

crime within the State, shall be concealed on board said

vessel. Such inspection shall be made within

twelve hours of the time of departure of such vessel

from the waters of Virginia, and may be made in any bay,

river, creek, or other water-course of the State,

provided, however, that steamers plying as regular

packets, between ports in Virginia and those north of,

and outside of the capes of Virginia, shall be inspected

at the port of departure nearest Old Point Comfort.

(5.) A vessel so inspected and getting under way, with

intent to leave the waters of the State, if she returns

to an anchorage above Black River Point, or within Old

Point Comfort, shall be again inspected and charged as

if an original case. If such vessel be driven back

by stress of weather to seek a harbor, she shall be

exempt from payment of a second fee, unless she holds

intercourse with the shore.

(6.) If, after searching the vessel, the inspector see

no just cause to detain her, he shall give to the

captain a certificate to that effect. If, however,

upon such inspection, or in any other manner, any slave

or person held to service or labor, or any person

charged with any crime, he found on board of any vessel

whatever, for the purpose aforesaid, or said vessel be

detected in the act of leaving this commonwealth with

any such slave or person on board, or otherwise

violating the provisions of this act, he shall attach

said vessel, and arrest all persons on board, to be

delivered up to the sergeant or sheriff of the nearest

port in this commonwealth, to be dealt with according to

law.

[Pg. 279]

(7.) If any inspector or other officer be opposed, or

shall have reason to suspect that he will be opposed or

obstructed in the discharge of any duty required of him

under this act, he shall have power to summon and

command the force of any county or corporation to aid

him in the discharge of such duty, and every person who

shall resist, obstruct, or refuse to aid any inspector

or other officer in the discharge of such duty, shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, upon conviction

thereof, shall be fined and imprisoned as in other cases

of misdemeanor.

(8.) For every inspection of a vessel under this law,

the inspector, or other officer shall be entitled to

demand and receive the sum of five dollars; for the

payment of which such vessel shall be liable, and the

inspector or other officer may seize and hold her until

the same is paid, together with all charges incurred in

taking care of the vessel, as well as in enforcing the

payment of the same. Provided, that steam packets

trading regularly between the waters of Virginia and

ports north of and beyond the capes of Virginia, shall

pay not more than five dollars for each inspection under

the provisions of this act; provided, however, that for

every inspection of a vessel engaged in the coal trade,

the inspector shall not receive a greater sum than two

dollars.

(9.) Any inspector or other person apprehending a slave

in the act of escaping from the state, on board a vessel

trading to or belonging to a non slave-holding state, or

who shall give information that will lead to the

recovery of any slave, as aforesaid, shall be entitled

to a reward of One Hundred Dollars, to be paid by the

owner of such slave, or by the fiduciary having charge

of the estate to which such slave belongs; and if the

vessel be forfeited under the provisions of this act, he

shall be entitled to one-half of the proceeds arising

from the sale of the vessel; and if the same amounts to

one hundred dollars, he shall not receive from the owner

the above reward of one hundred dollars.

(10.) An inspector permitting a. slave to escape for

the want of proper exertion, or by neglect in the

discharge of his duty, shall be fined One Hundred

Dollars; or if for like causes he permit a vessel, which

the law requires him to inspect, to leave the state

without inspection, he shall be fined not less than

twenty, nor more than fifty dollars, to be recovered by

warrant by any person who will proceed against him.

(11.) No pilot acting under the authority of the laws

of the state, shall pilot out of the jurisdiction of

this state any such vessel as is described in this act,

which has not obtained and exhibited to him the

certificate of inspection hereby required; and if any

pilot shall so offend, he shall forfeit and pay not less

than twenty, or more than fifty dollars, to be recovered

in the mode prescribed in the next preceding section of

this act.

(12.) The courts of the several counties or

corporations situated on the Chesapeake Bay, or its

tributaries, by an order entered on record, may

[Pg. 280]

appoint one or more inspectors, at such place or places

within their respective districts as they may deem

necessary, to prevent the escape or for the recapture of

slaves attempting to escape beyond the limits of the

state, and to search or otherwise examine all vessels

trading to such counties or corporations. The

expenses in such cases to be provided for by a levy on

negroes now taxed by law; but no inspection by county or

corporation officers thus appointed, shall supersede the

inspection of such vessels by pilots and other

inspectors, as specially provided for in this act.

(13.) It shall be lawful for the county court of any

county, upon the application of five or more

slave-holders, residents of the counties where the

application is made, by an order of record, to designate

one or more police stations in their respective

counties, and a captain and three or more other persons

as a police patrol on each station, for the recapture of

fugitive slaves; which patrol shall be in service at

such times, and such stations as the court shall direct

by their order aforesaid; and the said court shall allow

a reason able compensation, to be paid to the members of

such patrol; and for that purpose, the said court may

from time to time direct a levy on negroes now taxed by

law, at such rate per capita as the court may think

sufficient, to be collected and accounted for by the

sheriff as other county levies, and to be called, “The

fugitive slave tax.” The owner of each fugitive

slave in the act of escaping beyond the limits of the

commonwealth, to a non-slave-holding state, and captured

by the patrol aforesaid, shall pay for each slave over

fifteen, and under forty-five years old, a reward of One

Hundred dollars; for each slave over five, and under

fifteen years old, the sum of sixty dollars; and for all

others, the sum of forty dollars. Which reward

shall be divided equally among the members of the patrol

retaking the slave and actually on duty at the time; and

to secure the payment of said reward, the said patrol

may retain possession and use of the slave until the

reward is paid or secured to them.

(14.) The executive of this State may appoint one or

more inspectors for the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers,

if he shall deem it expedient, for the due execution of

this act. The inspectors so appointed to perform

the same duties, and to be invested with the same powers

in their respective districts, and receive the same

fees, as pilots acting as inspectors in other parts of

the State. A vessel subject to inspection under

this law, departing from any of the above-named counties

or rivers on her voyage to sea, shall be exempted from

the payment of a fee for a second inspection by another

officer, if provided with a certificate from the proper

inspecting officer of, that district; but if, after

proceeding on her voyage, she returns to the port or

place of departure, or enters any other port, river, or

roadstead in the State, the said vessel shall be again

inspected, and pay a fee of five dollars, as if she had

undergone no previous examination and received no

previous certificate.

[Pg. 281]

If driven by, stress of weather

to seek a harbor, and she has no intercourse with the

shord, then, and in that case, no second fee shall be

paid by said vessel.

(15). For the better execution of the provisions of

this act, in regard to he inspection of vessels, the

executive is hereby authorized and directed to appoint a

chief inspector, to reside at Norfolk, whose duty it

shall be, to direct and superintend the police, agents,

or inspectors above referred to. He shall keep a

record of all vessels engaged in the piloting business,

together with a list of such persons as may be employed

as pilots and inspectors under this law. The owner

or owners of each boat shall make a monthly report to

him, of all vessels inspected by persons attached to

said pilot boats, the names of such vessels, the owner

or owners thereof, and the places where owned or

licensed, and where trading to or from, and the business

in which they are engaged, together with a list of their

crews. Any inspector failing to make his report to

the chief inspector, shall pay a fine of twenty dollars

for each such failure, which fine shall be recovered by

warrant, before a justice of the county or corporation.

The chief inspector may direct the time and station for

the cruise of each pilot boat, and perform such other

duty as the Governor may designate, not inconsistent

with the other provisions of this act. He shall

make a quarterly return to the executive of all the

transactions of his department, reporting to him any

failure or refusal on the part of inspectors to

discharge the duty assigned to them, and the Governor,

for sufficient cause, may suspend or remove from office

any delinquent inspector. The chief inspector

shall receive as his compensation, ten per cent. on all

the fees and fines received by the inspectors acting

under his authority, and may be removed at the pleasure

of the executive.

(16.) All fees and forfeitures imposed by this

act, and not otherwise specially provided for, shall go

one half to the informer, and the other be paid into the

treasury of the State, to constitute a fund, to be

called the “fugitive slave fund,” and to be used for the

payment of rewards awarded by the Governor, for the

apprehension of runaway slaves, and to pay other

expenses incident to the execution of this law, together

with such other purposes as may hereafter be determined

on by the General Assembly.

(17.) This act shall be in force from its passage.

_______________

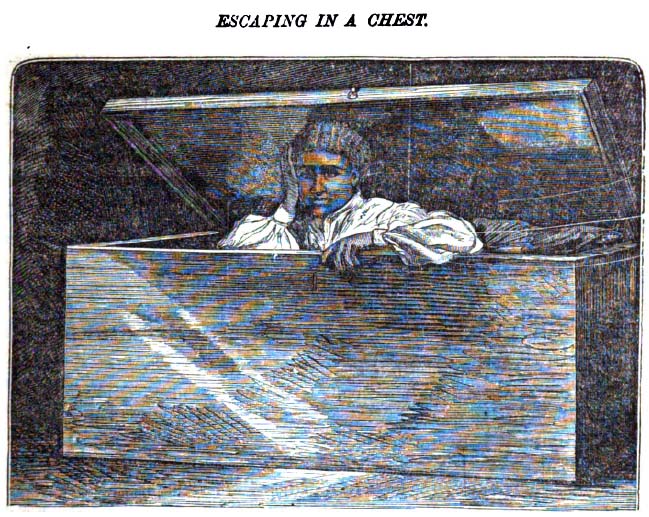

ESCAPING IN A CHEST

|

$150 REWARD.

Ran away from the subscriber, on Sunday night,

27th inst., my NEGRO GIRL. Lear Green,

about 18 years of age, black complexion,

round-featured, good-looking and ordinary size;

she had on and with her when she left, a

tan-colored silk bonnet, a dark plaid silk

dress, a light mouslin delaine, also one watered

silk cape and one tan colored cape. I have

reason to be confident that she was per- |

[Page 282]

| |

suaded off by a negro man named

Wm. Adams, black, quick spoken, 5 feet 10

inches high, a large scar on one side of his

face, running down in a ridge by the corner of

his mouth, about 4 inches long, barber by

trade, but works mostly about taverns, opening

oysters, &c. He has been missing about a

week; he had been heard to say he was going to

marry the above girl and ship to New York, where

it is said his mother resides. The above

reward will be paid if said girl is taken out of

the State of Maryland and delivered to me; or

fifty dollars if taken in the State of Maryland.

JAMES NOBLE,

m26-3t.

No. 153 Broadway, Baltimore |

LEAR GREEN,

so particularly advertised in the "Baltimore Sun" by

"James Noble," won for herself a strong claim to

a high place among the heroic women of the nineteenth

century. In regard to description and age the

advertisement is tolerably accurate, although her master

might have added, that her countenance was one of

Peculiar modesty and grace. Instead of being

"black," she was of a "dark-brown color." Of her

bondage she made the following statement: She was

owned by James Noble, a butter Dealer" of

Baltimore. He fell heir to Learby the will

of his wife's mother, Mrs. Rachel Howard, by whom

she had previously been owned. Lear was but

a mere child when she came into the hands of

Noble's family. She, therefore, remembered but

little of her old mistress. Her young mistress,

however, had made a lasting impression upon her mind;

for she was very exacting and oppressive in regard to

the tasks she was daily in the habit of laying upon

Lear’s shoulders, with no disposition whatever to

allow her any liberties. At least Lear was never

indulged in this respect. In this situation a

young man by the name of William Adams

proposed marriage to her. This offer she was

inclined to accept, but disliked the idea of being

encumbered with the chains of slavery and the duties of

a family at the same time.

After a full consultation with her mother and also her

intended upon the matter, she decided that she must be

free in order to fill the station of a wife and mother.

For a time dangers and difficulties in the way of escape

seemed utterly to set at defiance a hope of success.

Whilst every pulse was beating strong for liberty, only

one chance seemed to be left, the trial of which

required as much courage as it would to endure the

cutting off the right arm or plucking out the right eye.

An old chest of substantial make, such as sailors

commonly use, was procured. A quilt, a pillow, and

a few articles of raiment, with a small quantity of food

and a bottle of water were put in it, and Lear

placed therein; strong ropes were fastened around the

chest and she was safely stowed amongst the ordinary

freight on one of the Erricson line of steamers.

Her intended’s mother, who was a free woman, agreed to

come as a passenger on the same boat. How could

she refuse? The prescribed rules of the Company

assigned colored passengers to the deck. In this

instance it was exactly where this guardian and mother

desired to be - as near the chest as possible.

Once or twice, during the silent watches of the night,

she was drawn irresisti-

[Page 283]

bly to the chest, and could not refrain from venturing

to untie the rope and raise the lid a little, to see if

the poor child still lived, and at the

same time to give her a breath of fresh air.

Without uttering a whisper, that frightful moment, this

office was successfully performed. That the

silent prayers of this oppressed young woman, together

with her faithful protector’s, were momentarily

ascending to the ear of the good God above, there

can be no question. Nor is it to be doubted for a

moment but that some ministering angel aided the mother

to unfasten the rope, and at the same time nerved the

heart of poor Lear to endure the trying ordeal of

her perilous situation. She declared that she had

no fear. After she

had passed eighteen hours in the chest, the steamer

arrived at the wharf in Philadelphia, and in due time

the living freight was brought off the boat, and at

first was delivered at a house in Barley street,

occupied by particular friends of the mother.

Subsequently chest and freight were removed to the

residence of the writer, in whose family she remained

several days under the protection and care of the

Vigilance Committee.

Such hungering and thirsting for liberty, as was

evinced by Lear Green, made the efforts of the

most ardent friends, who were in the habit of aiding

fugitives, seem feeble in the extreme. Of all the

heroes in Canada, or out n of it, who have purchased

their liberty by downright bravery, through perils the

most hazardous, none deserve more praise than Lear

Green.

She remained for a time in this family, and was then

forwarded to El mira. In this place she was married to

William Adams, who has bee

[Page 284]

previously alluded to. They never went to Canada,

but took up their permanent abode in Elmira. The

brief space of about three years only was allotted her

in which to enjoy freedom, as death came and terminated

her career. About the time of this sad occurrence,

her mother-in-law died in this city. The

impressions made by both mother and daughter can never

be effaced. The chest in which Lear escaped has

been preserved by the writer as a rare trophy, and her

photograph taken, while in the chest, is an excellent

likeness of her and, at the same time, a fitting

memorial.

_______________

ISAAC WILLIAMS, HENRY BANKS, AND KIT NICKLESS.

MONTHS IN A CAVE. - SHOT BY SLAVE-HUNTERS.

Rarely were three travelers

from the house of bondage received at the Philadelphia

station whose narratives were more interesting than

those of the above-named individuals. Before escaping

they had encountered difficulties of the most trying

nature. No better material for dramatic effect

could be found than might have been gathered from the

incidents of their lives and travels. But all that

we can venture to introduce here is the brief account

recorded at the time of their sojourn at the

Philadelphia station when on their way to Canada in

1854. The three journeyed together. They had

been slaves together in the same neighborhood. Two

of them had shared the same den and cave in the woods,

and had been shot, captured, and confined in the same

prison; had broken out of prison and again escaped;

consequently their hearts were thoroughly cemented in

the hope of reaching freedom together.

ISAAC was

a stout-made young man, about twenty-six years of age,

possessing a good degree of physical and mental ability.

Indeed his intelligence forbade his submission to the

requirements of Slavery, rendered him unhappy and led

him to seek his freedom. He owed services to D.

Fitehhugh up to within a short time before he

escaped. Against Fitchhugh he made grave

charges, said that he was a “hard, bad man.” It is

but fair to add that Isaac was similarly regarded by his

master, so both were dissatisfied with each other.

But the master had the advantage of Isaac, he

could sell him. Isaac, however, could turn

the table on his master, by running off. But the

master moved quickly and sold Isaac to Dr.

James, a negro trader. The trader designed

making a good speculation out of his investment:

Isaac determined that he should be disappointed;

indeed that he should lose every dollar that he paid for

him. So while the doctor was planning where and

how he could get the best price for him, Isaac

was planning how and where he might safely get beyond

his reach. The time for planning and acting with

Isaac was, however, exceedingly short. He

[Page 285]

was daily expecting to be called upon to take his

departure for the South. In this situation he made

known his condition to a friend of his who was in a.

precisely similar situation; had lately been sold just

as Isaac had to the same trader James. So

no argument was needed to convince his friend and

fellow-servant that if they meant to be free they would

have to set off immediately.

That night Henry Banks and Isaac

Williams started for the woods together,

preferring to live among reptiles and wild animals,

rather than be any longer at the disposal of Dr.

James. For two weeks they successfully

escaped their pursuers. The woods, however, were

being hunted in every direction, and one day the

pursuers came upon them, shot them both, and carried

them to King George’s Co. jail. The jail being an

old building had weak places in it; but the prisoners

concluded to make no attempt to break out while

suffering badly from their wounds. So they

remained one month in confinement. All the while

their brave spirits under suffering grew more and more

daring. Again they decided to strike for freedom,

but where to go, save to the woods, they had not the

slightest idea. Of course they had heard, as most

slaves had, of cave life, and pretty well understood all

the measures which had to be resorted to for security

when entering upon so hazardous an undertaking.

They concluded, however, that they could not make their

condition any worse, let circumstances be what they

might in this respect. Having discovered how they

could break jail, they were not long in accomplishing

their purpose, and were out and off to the woods again.

This time they went far into the forest, and there they

dug a cave, and with great pains had every thing so

completely arranged as to conceal the spot entirely.

In this den they stayed three months. Now and then

they would manage to secure a pig. A friend also

would occasionally serve them with a meal. Their

sufferings at best were fearful; but great as they were,

the thought of returning to Slavery never occurred to

them, and the longer they stayed in the woods, the

greater was their determination to be free. In the

belief that their owner had about given them up they

resolved to take the North Star for a pilot, and try in

this way to reach free land.

KIT, an old friend in time of

need, having proved true to them in their cave, was

consulted. He fully appreciated their heroism, and

determined that he would join them in the undertaking,

as he was badly treated by his master, who was called

General Washington, a common farmer, hard

drinker, and brutal fighter, which Kit’s poor

back fully evinced by the marks it bore. Of course

Isaac and Henry were only too willing to

have him ac company them.

In leaving their respective homes they broke kindred

ties of the tenderest nature. Isaac had a

wife, Eliza, and three children, Isaac,

Estella, and Ellen, all owned by Fitchhugh.

Henry was only nineteen, single, but left

[Page 286]

parents, brothers, and sisters, all owned by different

slave-holders. Kit had a wife, Matilda,

and three children, Sarah Ann, Jane

Frances, and Ellen, slaves.

_______________

ARRIVAL

OF FIVE FROM THE EASTERN SHORE OF MARYLAND

CYRUS MITCHELL,

alias JOHN STEEL;

JOSHUA HANDY,

alias HAMBLETON HAMBY;

CHARLES DULTON, alias WILLIAM ROBINSON;

EPHRAIM HUDSON, alias JOHN SPRY;

FRANCIS MOLOCK, alias

THOMAS JACKSON; all in "good order" and full of hope.

The following letter from the

fearless friend of the slave, Thomas Garrett,

is a specimen of his manner of dispatching Underground

Rail Road business. He used Uncle Sam’s

mail, and his own name, with as much freedom as though

he had been President of the Pennsylvania Central Rail

Road, instead of only a conductor and stockholder on the

Underground Rail Road.

RESPECTED

FRIEND: - WILLIAM STILL, I

send on to thy care this evening by Rail Road, 5

able-bodied men, on their way North; receive them as the

Good Samaritan of old and oblige thy friend,

THOMAS GARRETT.

The "able-bodied men" duly

arrived, and were thus recorded on the Underground Rail

Road books as trophies of the success of the friends of

humanity.

CYRUS is

twenty-six years of age, stout, and unmistakably dark,

and was owned by James K. Lewis, a tore-keeper,

and a "hard master." He kept slaves for the

express purpose of hiring them out, and it seemed to

afford him as much pleasure to receive the hard-earned

dollars of his bondmen as if he had labored for them

with his own hands. "It mattered not, how mean a

man might be," if he would pay the largest price, he was

the man whom the store-keeper preferred to hire to.

This always caused Cyrus to dislike him.

Latterly he had been talking of moving into the State of

Virginia. Cyrus disliked this talk

exceedingly, but he “said nothing to the white people”

touching the matter. However, he was not long in

deciding that such a move would be of no advantage to

him; indeed, he had an idea if all was true that he had

heard about that place, he would be still more miserable

there, than he had ever been under his present owner.

At once, he decided that he would move towards Canada,

and that he would be fixed in his new home before his

master got off to Virginia, unless he moved sooner than

Cyrus expected him to do. Those nearest of

kin, to whom he

[Page 287]

felt most tenderly allied, and from whom he felt that it

would be hard to part, were his father and mother.

He, however, decided that he should have to leave them.

Freedom, he felt, was even worth the giving up of

parents.

Believing that company was desirable, he took occasion

to submit his plan to certain friends, who were at once

pleased with the idea of a trip on the Underground Rail

Road, to Canada, etc; and all agreed to join him.

At first, they traveled on foot; of their subsequent

travel, mention has already been made in friend

Garrett’s epistle.

JOSHUA

is

about twenty-seven years of age, quite stout, brown

color, and would pass for an intelligent farm hand.

He was satisfied never to wear a yoke again that some

one else might reap the benefit of his toil. His

master, Isaac Harris, he denounced as a

“drunkard.” His chief excuse for escaping, was

because Harris had “sold” his “only brother.”

He was obliged to leave his father and mother in the

hands of his master.

CHARLES

is twenty-two years of age, also stout, and well-made,

and apparently possessed all the qualifications for

doing a good day's work on a farm. He was held to

service by Mrs. Mary Hurley. Charles gave

no glowing account of happiness and comfort under the

rule of the female sex, indeed, he was positive in

saying that he had "been used rough." During the

present year, he was sold for $1200.

EPHRAIM

is twenty-two years of age, stout and athletic, one who

appears in every way fitted for manual labor or anything

else that he might be privileged to learn. John

Campbell Henry, was the name of the man whom he had

been taught to address as master, and for whose benefit

he had been compelled to labor up to the day he "took

out." In considering what he had been in Maryland

and how he had been treated all his life, he alleged

that John Campbell Henrywas a bad man." Not

only had Ephraim been treated badly by his master

but he had been hired out to a man no better than his

master, if as good. Ephraim left his mother

and six brothers and sisters.

FRANCIS

is twenty-one, an able-bodied "article," of dark color,

and was owned by James A. Waddell. All that

he could say of his owner, was, that he was a "hard

master," from whom he was very glad to escape.

_____________

SUNDRY

ARRIVALS, ABOUT AUGUST 1ST, 1855.

Arrival 1st.

Francis Hilliard

Arrival 2d. Louisa Harding, alias

Rebecca Hall.

Arrival. 3d. John Mackintosh.

Arrival 4th.

Maria Jane Houston.

[Page 288]

Arrival 5th. Miles Hoopes.

(or Hooper)

Arrival 6th. Samuel Miles, alias Robert

King.

Arrival 7th. James Henson, alias David

Caldwell.

Arrival 8th. Laura Lewis.

Arrival 9th. Elizabeth Banks.

Arrival 10th. Simon Hill.

Arrival 11th.

Anthony and Albert Brown

Arrival 12th. George Williams and Charles

Holladay

Arrival 13th.

William Govan

While none in this catalogue

belonged to the class whose daring adventures rendered

their narratives marvellous, nevertheless they

represented a very large number of those who were

continually on the alert to get rid of their captivity.

And in all their efforts in this direction they

manifested a marked willingness to encounter perils

either by land or water, by day or by night, to obtain

their God-given rights. Doubtless, even

among these names, will be found those who have been

supposed to be lost, and mysteries will be disclosed

which have puzzled scores of relatives longing and

looking many years in vain to ascertain the whereabouts

of this or that companion, brother, sister, or friend.

So, if impelled by no other consideration than the hope

of consoling this class of anxious inquirers, this is a

sufficient justification for not omitting them entirely,

notwithstanding the risk of seeming to render these

pages monotonous.

ARRIVAL No. 1. First on

this record was a young mulatto woman, twenty-nine years

of age - orange color, who could read and write very

well, and was unusually intelligent and withal quite

handsome. She was known by the name of

FRANCIS

HILLIARD, and escaped from Richmond, Va., where she

was owned by Beverly Blair. The

owner hired her out to a man by the name of Green,

from whom he received seventy dollars per annum.

Green allowed her to hire herself for the same

amount, with the understanding that Frances

should find all her own clothes, board herself and find

her own house to live in. Her husband, who was

also a slave, had fled nearly one year previous, leaving

her widowed, of course. Notwithstanding the above

mentioned conditions, under which she had the privilege

of living, Frances said that she “had been used

well.” She had been sold four times in her life.

In the first instance the failure of her master was

given as the reason of her sale. Subsequently she

was purchased and sold by different traders, who

designed to speculate upon her as a “ fancy article.”

They would dress her very elegantly, in order to show

her off to the best advantage possible, but it appears

that she had too much regard for her husband and her

honor, to consent to fill the positions which had been

basely assigned her by her owners.

Frances assisted her husband to escape from his

owner—Taits—and was

[Page 289]

never contented until she succeeded in following him to

Canada. In escaping, she left her mother, Sarah

Corbin, and her sister, Maria. On

reaching the Vigilance Committee she learned an about

her husband. She was conveyed from Richmond

secreted on a steamer under the care of one of the

colored hands on the boat. From here she was

forwarded to Canada at the expense of the Committee.

Arriving in Toronto, and not finding her hopes fully

realized, with regard to meeting her husband, she wrote

back the following letter:

MY DEAR

MR.

STILL:—Sir—I

take the opportunity of writing you a few lines to

inform you of my health. I am very well at

present, and hope that when these few lines reach you

they may find you enjoying the same blessing. Give

my love to Mrs. Still and all the

children, and also to Mr. Swan, and tell

him that he must give you the money that he has, and you

will please send it to me, as I have received a letter

from my husband saying that I must come on to him as

soon as I get the money from him. I cannot go to

him until I get the money that Mr. Swan

has in hand. Please tell Mr. Caustle

that the clothes he spoke of .my mother did not know

anything about them. I left them with Hinson

Brown and he promised to give them to Mr.

Smith. Tell him to ask Mr. Smith to

get them from Mr. Brown for me, and when I

get settled I will send him word and he can send them to

me. The letters that were sent to me I received

them all. I wish you would send me word if Mr.

Smith is on the boat yet—if he is please write me

word in your next letter. Please send me the money

as soon as you possibly can, for I am very anxious to

see my husband. I send to you for I think you will

do what you can for me. No more at present, but

remain

| |

Yours truly,

|

FRANCES HILLIARD.

|

Send me word if Mr.

Caustle had given Mr. Smith the money

that he promised to give him.

For one who had to steal the art of

reading and writing, her letter bears studying.

ARRIVAL No. 2.

LOUISA HARDING, alias REBECCA HALL.

Louisa was a mulatto girl, seventeen years of age.

She reported herself from Baltimore, where she had been

owned by lawyer Magill. It might be

said that she also possessed great personal attractions

as an “article” of much value in the eye of a trader.

All the near kin whom she named as having left he hind,

consisted of a mother and a brother.

ARRIVAL No. 3.

JOHN MACKINTOSH. John’s history is short.

He represented himself as having arrived from Darien,

Georgia, where he had seen “hard times.” Age,

forty-four; This is all that was recorded of John,

except the expenses met by the Committee.

ARRIVAL No. 4.

MARIA JANE HOUSTON. The little State of

Delaware lost in the person of Maria, one of her

nicest-looking bond-maids. She had just arrived at

the age of twenty-one, and felt that she had already

been sufficiently wronged. She was a tall, dark,

young woman, from the neighborhood of Cantwell’s Bridge.

Although she had no horrible tales of suffering to

relate, the Committee regarded her as well worthy of a

[Page 290]

ARRIVAL NO. 5.

MILES HOOPER. This subject came from North Carolina; he

was owned by George Montigue, who lived at

Federal Mills, was a decided opponent to the no-pay

system, to flogging, and selling likewise. In fact

nothing that was auxiliary to Slavery was relished by

him. Consequently he concluded to leave the place

altogether. At the time that Miles took

this stand he was twenty-three years of age, a

dark-complexioned man, rather under the medium height,

physically, but a full-grown man mentally. “My

owner was a hard man,” said Miles, in speaking of

his characteristics. His parents, brothers, and

sisters were living, at least he had reason to believe

so, although they were widely scattered.

ARRIVAL No. 6.

SAMUEL MILES, alias ROBERT KING.

Samuel was a representative of Revel’s Neck,

Somerset Co., Md. His master he regarded as a “

very fractious man, hard to please.” The cause of

the trouble or un pleasantness, which resulted in

Samuel’s Underground adventure, was traceable to his

master’s refusal to allow him to visit his wife.

Not only was Samuel denied this privilege, but he

was equally denied all privileges. His master

probably thought that Sam had no mind, nor any

need of a wife. Whether this was really so or not,

Sam was shrewd enough to “ leave his old master

with the bag to hold,” which was sensible.

Thirty-one years of Samuel’s life were passed in

Slavery, ere he escaped. The remainder of his days

he felt bound to have the benefit of himself. In

leaving home he had to part with his wife and one child,

Sarah and little Henry, who were

fortunately free.

On arriving in Canada Samuel wrote back for his

wife, &c., as follows:

| |

|

ST. CATHARINES,

C. W., Aug. 20th, 1855. |

To MR.

WM. STILL,

DEAR FRIEND:—It

gives me pleasure to inform you that I have had the good

fortune to reach this northern Canaan. I got here

yesterday and am in good health and happy in the

enjoyment of Freedom, but am very anxious to have my

wife and child here with me.

I wish you to write to her immediately on receiving

this and let her know where I am you will recollect her

name Sarah Miles at Baltimore on the

corner of Hamburg and Eutaw streets. Please

encourage her in making a start and give her the

necessary directions how to come. She will please

to make the time as short as possible in getting through

to Canada. Say to my wife that I wish her to write

immediately to the. friends that I told her to address

as soon as she hears from me. Inform her that I

now stop in St. Catharines near the Niagara Falls that I

am not yet in business but expect to get into business

very soon—That I am in the enjoyment of good health and

hoping that this communication may find my affectionate

wife the same. That I have been highly favored

with friends throughout my journey I wish my wife to

write to me as soon as she can and let me know how soon

I may expect to see her on this side of the Niagara

River. My wife had better call on Dr.

Perkins and perhaps he will let her have the money

he had in charge for me but that I failed of receiving

when I left Baltimore. Please direct the letter

for my wife to Mr. George Lister,

in Hill street between Howard and Sharp.

My compliments to all enquiring friends.

| |

Very respectfully yours,

|

SAMUEL MILES. |

P. S. Please send the thread

along as a token and my wife will understand that all is

right.

S. M.

[Page 291]

ARRIVAL No. 7.

JAMES HENSON, alias DAVID CALDWELL. James fled from

Cecil Co., Md. He claimed that he was entitled to

his freedom ac cording to law at the age of

twenty-eight, but had been unjustly deprived of it.

Having waited in vain for his free papers for four

years, he suspected that he was to be dealt with in a

manner similar to many others, who had been willed free

or who had bought their time, and had been shamefully

cheated out of their freedom. So in his judgment

he felt that his only hope lay in making his escape on

the Underground Rail Road. He had no faith

whatever in the man who held him in bondage, Jacob

Johnson, but no other charges of ill treatment,

&c., have been found against said Johnson on the

books, save those alluded to above. James

was thirty-two years of age, stout and well

proportioned, with more than average intelligence and

resolution. He left a wife and child, both

free.

ARRIVAL No. 8.

LAURA LEWIS. Laura arrived from Louisville,

Kentucky. She had been owned by a widow woman

named Lewis, but as lately as the previous March

her mistress died, leaving her slaves and other property

to be divided among her heirs. As this would

necessitate a sale of the slaves, Laura

determined not to be on hand when the selling day "came,

so she took time by the forelock and left. Her

appearance indicated that she had been among the more

favored class of slaves. She was about twenty-five

years of age, quite stout, of mixed blood, and

intelligent, having traveled considerably with her

mistress. She had been North in this capacity.

She left her mother, one brother, and one sister in

Louisville.

ARRIVAL No. 9.

ELIZABETH BANKS, from near Easton, Maryland. Her lot

had been that of an ordinary slave. Of her

slave-life nothing of interest was recorded. She

had escaped from her owner two and a half years prior to

coming into the hands of the Committee, and had been

living in Pennsylvania pretty securely as she had

supposed, but she had been awakened to a. sense of her

danger by well grounded reports that she was pursued by

her claimant, and would. be likely to be captured if she

tarried short of Canada. With such facts staring

her in the face she was sent to the Committee for

counsel and protection, and by them she was forwarded on

in the usual way. She was about twenty-five years

of age, of a dark, and spare structure.

ARRIVAL No. 10.

SIMON HILL. This fugitive had escaped from Virginia.

The usual examination was made, and needed help given

him by the Com mittee, who felt satisfied that he was a

poor brother who had been shame fully wronged, and that

he richly deserved sympathy. He was aided and

directed Canada-ward. He was a very humble-looking

specimen of the peculiar institution, about twenty-five

years of age, medium size, and of a dark hue.

ARRIVAL No. 11.

ANTHONY and ALBERT BROWN (brothers),

JONES ANDERSON and ISAIAH.

[Page 292]

This party escaped from Tanner's Creek, Norfolk,

Virginia, where they had been owned by John and Henry

Holland, oystermen. As slaves they alleged

that they had been subjected to very brutal treatment

from their profane and ill-natured owners. Not

relishing this treatment, Albert and Anthony

came to the conclusion that they understood boating well

enough to escape by water. They accordingly

selected one of their master’s small oyster-boats, which

was pretty-well rigged with sails, and off they started

for a Northern Shore. They proceeded on a part of

their voyage merely by guess work, but landed safely,

however, about twenty-five miles north of Baltimore,

though, by no means, on free soil. They had no

knowledge of the danger that they were then in, but they

were persevering, and still determined to make their way

North, and thus, at last, success attended their

efforts. Their struggles and exertions having been

attended with more of the romantic and tragical elements

than had characterized the undertakings of any of the

other late passengers, the Committee felt inclined to

make a fuller notice of them on the book, yet failed to

do them justice in this respect.

The elder brother was twenty-nine, the younger

twenty-seven. Both were mentally above the average

run of slaves. They left wives in Norfolk, named

Alexenia and Ellen. While Anthony

and Albert, in seeking their freedom, were forced

to sever their connections with their companions, they

did not forget them in Canada.

How great was their delight in freedom, and tender

their regard for their wives, and the deep interest they

felt for their brethren and friends generally, may be

seen from a perusal of the following letters from them:

| |

|

HAMILTON,

March 7th, 1856. |

MR. WM.

STILL: - Sir: -

I now take the opportunity of writing you a few lins

hoping to find yourself and famly wellaas thee lines

leves me at present, myself and brother, Anthony

& Albert brown’s respects. We have

spent quite agreeable winter, we ware emploied in the

new hotel name Anglo american, wheare we wintered and

don very well, we also met with our too frends ho came

from home with us, Jonas anderson and

lzeas, now we are all safe in hamilton, I wish to

cale you to youre prommos, if convenient to write to

Norfolk, Va, for me, and let my wife mary Elen

Brown, no where I am, and my brothers wife

Elickzener Brown, as we have never heard a

word from them since we left, tel them that we found our

homes and situation in canady much better than we

expected, tel them not to think hard of us, we was boun

to flee from the rath to come, tel them we live in the

hopes of meting them once more this side of the grave,

tel them if we never ‘ more see them, we hope to meet

them in the kingdom of heaven in pece, tel them to

remember my love to my eherch and brethren, tel them I

find there is the same prayer hearing God heare as there

is in old Va; tel them to remember our love to all the

enquiring frends, I have written sevrel times but have

never reseived no answer, I find a gret meny of my old

accuaintens from Va., heare we are no ways lonesom,

Mr. Still, I have written to you once before,

but reseve no answer. Pleas let us hear from yon by any

means. Nothing more at present, but remane youre frends,

[Page 293]

| |

|

HAMILTON,

June 26th, 1856. |

MR. WM.

STILL—kine Sir—I am

happy to say to you that I have jus reserved my, letter

dated 5 of the present month, but previously had bin in

form las night by Mr. J., H. Hall, he had jus

reseved a letter from you stating that my wife was with

you, oh my I was so glad it case me to shed tears.

Mr. Still, I

cannot return you the thanks for the care of my wife,

for I am so Glad that I dont now what to say, you will

pleas start her for canaday. I am yet in hamilton,

C. W, at the city hotel, my brother and Joseph

anderson is at the angle american hotel, they send

there respects to you and family my self also, and a

greater part to my wife. I came by the way of

syracruse remember me to Mrs. logius, tel

her to writ back to my brothers wife if she is living

and tel her to com on tel her to send Joseph

Andersons love to his mother.

i now send her 10 Dollars and would send more but being

out of employment some of winter it pulls me back, you

will be so kine as to forward her on to me, and if life

las I will satisfie you at some time, before long.

Give my respects and brothers to Mr. John

Dennes, tel him Mr. Hills famly is

wel and send there love to them, I now bring my letter

to a close, And am youre most humble Servant,

P. S. I had given out the notion of ever seeing my wife

again, so I have not been attending the office, but am

truly sorry I did not, you mention in yours of Mr.

Henry lewey, he has left this city for Boston about

2 weeks ago, we have not herd from him yet.

ARRIVAL No. 12.

GEORGE WILLIAMS and

CHARLES HOLLADAY.

These two travelers were about the same age. They

were not, however, from the same neighborhood—they

happened to meet each other as they were traveling the

road. George fled from St. Louis,

Charles from Baltimore. George “owed service

” to Isaac Hill, a planter; he found no

special fault with his master’s treatment of him; but

with Mrs. Hill, touching this point, he

was thoroughly dissatisfied. She had treated him

“cruelly,” and it was for this reason that he was moved

to seek his freedom.

Charles, being a Baltimorean, had not far to

travel, but had pretty sharp hunters to elude.

His claimant, F. Smith, however, had only a term

of years claim upon him, which was within about two

years of being out. This contract for the term of

years, Charles felt was made without consulting

him, therefore he resolved to break it without

consulting his master. He also declined to have

anything to do with the Baltimore and Wilmington R. R.

Co., considering it a prescriptive institution, not

worthy of his confidence. He started on a fast

walk, keeping his eyes wide open, looking out for

slave-hunters on his right and left. In this way,

like many others, he reached the Committee safely and

was freely aided, thenceforth traveling in a first class

Underground Rail Road ear, till he reached his journey’s

end.

ARRIVAL No. 13.

WILLIAM GOVAN. Availing

himself of a passage on the schooner of Captain B.,

William left Petersburg, where he had been owned

by “Mark Davis, Esq., a retired

gentleman,” rather, a retired negro trader.

[Page 294]

William was about

thirty-three years of age, and was of a bright orange

color. Nothing but an ardent love of liberty

prompted him to escape. He was quite smart, and a

clever-looking man, worth at least $1,000.

_______________

DEEP

FURROWS ON THE BACK.

THOMAS MADDEN.

Of all the passengers who had

hitherto arrived with bruised and mangled bodies

received at the hands of slave-holders, none brought a

back so shame fully lacerated by the lash as Thomas

Madden. Not a single spot had been exempted

from the excoriating cow-hide. A most bloody

picture did the broad back and shoulders of Thomas

present to the eye as he hared his wounds for

inspection. While it was sad to think, that

millions of men, women, and children throughout the

South were liable to just such brutal outrages as

Thomas had received, it was a satisfaction to think,

that this outrage had made a freeman of him.

He was only twenty-two years of

age, but that punishment convinced him that he was fully

old enough to leave such a master as E. Ray, who

had almost murdered him. But for this treatment,

Thomas might have remained in some degree

contented in Slavery. He was expected to look

after the fires in the house on Sunday mornings.

In a single instance desiring to be absent, perhaps for

his own pleasure, two boys offered to be his substitute.

The services of the boys were accepted, and this gave

offence to the master. This Thomas declared

was the head and front of his offending. His

simple narration of the circumstances of his slave life

was listened to by the Committee with deep interest and

a painful sense of the situation of slaves under the

despotism of such men as Ray.

After being cared for by the

Committee he was sent on to Canada. When there he

wrote back to let the Committee know how he was faring,

the narrow escape he had on the way, and likewise to

convey the fact, that one named “Rachel,” left

behind, shared a large place in his affections.

The subjoined letter is the only correspondence of his

preserved:

| |

|

SAFFORD, June 1st, 1855, Niagara

districk. |

DEAR SIR

:—I set down to inform you that I take the liberty to

rite for a frend to inform you that he is injoying good

health and hopes that this will finde you the same he

got to this cuntry very well except that in Albany he

was vary neig taking back to his cald home but escaped

and when he came to the suspention bridg he was so glad

that he run for freadums shore and when he arived it was

the last of october and must look for sum wourk for the

winter he choped wood until Feruary times are good but

money is scarce he thinks a great deal of the girl he

left behind him he thinks that there is non like her

here non so hansom as his Rachel right and let him hear

from you as soon as convaniant no more at presant but

remain yours,

[Page 295]

"PETE

MATTHEWS," ALIAS SAMUEL SPARROWS.

I MIGHT AS WELL BE IN THE PENITENTIARY, &C."

Up to the age of thirty-five “Pete”

had worn the yoke steadily, if not patiently under

William S. Matthews, of Oak Hall, near

Temperaneeville, in the State of Virginia. Pete

said that his “ master was not a hard man," but the man

to whom he “was hired, George Matthews,

was a very cruel man.” “I might as well be in the

penitentiary as in his hands,” was his declaration.

One day, a short while before

Pete “took out,” an ox broke into the truck

patch, and helped himself to choice delicacies, to the

full extent of his capacious stomach, making sad havoc

with the vegetables generally. Peter's

attention being directed to the ox, he turned him out,

and gave him what he considered proper chastisement,

according to the mischief he had done. At this

liberty taken by Pete, the master became furious.

“He got his gun and threatened to shoot him.”

“Open your month if you dare, and I will put the whole

load into you,” said the enraged master. "He took

out a large dirk-knife, and attempted to stab me, but I

kept out of his way," said Pete.

Nevertheless the violence of the master did not abate

until he had beaten Pete over the head and body

till he was weary, inflicting severe injuries. A

great change was at once wrought in Pete’s mind.

He was now ready to adopt any plan that might hold out

the least encouragement to escape. Having capital

to the amount of four dollars only, he felt that he

could not do much towards employing a conductor, but he

had a good pair of legs, and a heart stout enough to

whip two or three slave-catchers, with the help of a

pistol. Happening to know a man who had a pistol

for sale, he went to him and told him that he wished to

purchase it. For one dollar the pistol became

Pete’s property. He had but three dollars

left, but he was determined to make that amount answer

his purposes under the circumstances. The last

cruel beating maddened him almost to desperation,

especially when he remembered how he had been compelled

to work hard night and day, under Matthews.

Then, too, Peter had a wife, whom his master

prevented him from visiting; this was not among the

least offences with which Pete charged his

master. Fully bent on leaving, the following

Sunday was fixed by him on which to commence his

journey.

The time arrived and Pete

bade farewell to Slavery, resolved to follow the North

Star, with his pistol in hand ready for action.

After traveling about two hundred miles from home he

unexpectedly had an opportunity of using his pistol.

To his astonishment he suddenly came face to face with a

former master, whom he had not seen for a long time.

Pete desired no friendly intercourse with him

whatever; but be perceived that his old

[Page 296]

master recognized him and was bent upon stopping him.

Pete held on to his pistol, but moved as fast as

his wearied limbs would allow him, in an opposite

direction. As he was running, Pete

cautiously, cast his eye over his shoulder, to see what

had become of his old master, when to his amazement, he

found that a regular chase was being made after him.

Need of redoubling his pace was quite obvious. In

this hour of peril, Pete's legs saved him.

After this signal leg-victory,

Pete had more confidence in his “under

standings,” than he had in his old pistol, although he

held on to it until he reached Philadelphia, where he

left it in the possession of the Secretary of the

Committee. Considering it worth saving simply as a

relic of the Underground Rail Road, it was carefully

laid aside. Pete was now christened

Samuel Sparrows. Mr. Sparrows

had the rust of Slavery washed off as clean as possible

and the Committee furnishing him with clean clothes,: I

ticket, and letters of introduction, started him on

Canada-ward, looking quite respectable. And

doubtless he felt even more so than he looked; free air

had a powerful effect on such passengers as Samuel

Sparrows.

The unpleasantness which grew

out of the mischief done by the ox on George

Matthews’ farm took place the first of October,

1855. Pete may be described as a man of

unmixed blood, well-made, and intelligent.

_______________

"MOSES"

ARRIVES WITH SIX PASSENGERS.

NOT ALLOWED TO SEEK A MASTER;" - "VERY

DEVILISH," - FATHER "LEAVES TWO LITTLE SONS;" - "USED

HARD;" - "FEARED FALLING INTO THE HANDS OF YOUNG HEIRS,"

ETC. JOHN CHASE, alias DANIEL FLOYD;

BENJAMIN ROSS, alias

JAMES STEWART; HENRY ROSS,

alias LEVIN STEWART; PETER

JACKSON, alias STAUNCH TILGHMAN; JANE KANE,

alias

CATHARINE KANE, AND ROBERT ROSS.

The coming of these passengers

was heralded by Thomas Garrett as follows:

THOMAS GARRETT'S LETTER

| |

|

WILMINGTON,

12mo. 29th, 1854 |

ESTEEMED

FRIEND, J. MILLER

MCKIM:-We

made arrangements last night, and sent away Harriet

Tubman, with six men and one woman to Allen Agnew’s, to

be forwarded across the country to the city. Harriet,

and one of the men had worn their shoes 05 their feet,

and I gave them two dollars to help fit them out, and

directed a carriage to be hired at my expense, to take

them out, but do not yet know the expense. I now have

two more from the lowest county in Maryland, on the

Peninsula, upwards of one hundred miles. I will try to

get one of our trusty colored men to take them tomorrow

morning to the Anti-slavery office. You can then

pass them on.

HARRIET TUBMAN

had been their "Moses," but not in the sense that

Andrew Johnson was the "Moses of the colored

people." She had faith-

[Page 297]

fully gone down into Egypt, and had delivered these six

bondmen by her own heroism. Harriet was a

woman of no pretensions, indeed, a more ordinary

specimen of humanity could hardly be found among the

most unfortunate-looking farm hands of the South.

Yet, in point of courage, shrewdness and disinterested

exertions to rescue her fellow-men, by making personal

visits to Maryland among the slaves, she was without her

equal.

Her success was wonderful. Time and again she

made successful visits to Maryland on the Underground

Rail Road, and would be absent for weeks, at a time,

running daily risks while making preparations for

herself and passengers. Great fears were

entertained for her safety, but she seemed wholly devoid

of personal fear. The idea of

being captured by slave hunters or slave-holders, seemed

never to enter her mind. She was apparently proof

against all adversaries. While she thus manifested

such utter personal indifference, she was much more

watchful with regard to those she was piloting.

Half of her time, she had the appearance of one asleep,

and would actually sit down by the road-side and go fast

asleep when on her errands of mercy through the South,

yet, she would not suffer one of her party to whimper

once, about “giving out and going back,” how ever

wearied they might be from hard travel day and night.

She had a very short and pointed rule or law of her own,

which implied death to any who talked of giving out and

going back. Thus, in an emergency she would give

all to understand that “times were very critical and

therefore no foolishness would be indulged in on the

road.” That several who were rather weak-kneed and

faint-hearted were greatly invigorated by Harriet’s

blunt and positive manner and threat of extreme

measures, there could be no doubt.

After having once enlisted, “they had to go through or

die.” Of course Harriet was supreme, and

her followers generally had full faith in her, and would

back up any word she might utter. So when she said

to them that “a live runaway could do great harm by

going back, but that a dead one could tell no secrets,”

she was sure to have obedience. Therefore, none

had to die as traitors on the “ middle passage.” It is

obvious enough, however, that her success in going into

Maryland as she did, was attributable to her adventurous

spirit and utter disregard of consequences. Her

like it is probable was never known before or since.

On examining the six passengers who came by this arrival

they were thus recorded:

December 29th, 1854—John is twenty years of age,

chestnut color, of spare build and smart. He fled

from a farmer, by the name of John Campbell

Henry, who resided at Cambridge, Dorchester Co.,

Maryland. On being interrogated relative to the

character of his master, John gave no very

amiable account of him. He testified that he was a

“hard man” and that he “owned about one hundred and

forty slaves and sometimes he would

[Page 298]

sell,” etc. John was one of the slaves who were

“hired out.” He “desired to have the privilege of

hunting his own master.” His desire was not

granted. Instead of meekly submitting, John

felt wronged, and made this his reason for running away.

This looked pretty spirited on the part of one so young

as John. The Committee's respect for him

was not a little increased, when they heard him express

himself.

BENJAMIN

was twenty-eight years of age, chestnut color, medium

size, and shrewd. He was the so-called property of

Eliza Ann Brodins, who lived near

Buckstown, in Maryland. Ben did not

hesitate to say, in unqualified terms, that his mistress

was “very devilish.” He considered his charges,

proved by the fact that three slaves (himself one of

them) were required to work hard and fare meagerly, to

support his mistress’ family in idleness and luxury.

The Committee paid due attention to his ex parte

statement, and was obliged to conclude that his

argument, clothed in common and homely language, was

forcible, if not eloquent, and that he was well worthy

of aid. Benjamin left his parents besides

one sister, Mary Ann Williamson,

who wanted to come away on the Underground Rail Road.

HENRY

left his wife, Harriet Ann, to be known in

future by the name of “Sophia Brown.“

He was a fellow-servant of Ben’s, and one of the

supports of Eliza A. Brodins.

HENRY

was

only twenty-two, but had quite an insight into matters

and things going on among slaves and slave-holders

generally, in country life. He was the father of

two small children, whom he had to leave behind.

PETER

was

owned by George Wenthrop, a farmer, living

near Cambridge, Md. In answer to the question, how

he had been used, he said “hard.” Not a pleasant

thought did he entertain respecting his master, save

that he was no longer to demand the sweat of Peter’s

brow. Peter left parents, who were free; he

was born before they were emancipated, consequently, he

was retained in bondage.

JANE,

aged twenty-two, instead of regretting that she had

unadvisedly left a kind mistress and indulgent master,

‘who had afforded her necessary comforts, affirmed that

her master, “Rash Jones, was the worst man

in the country.” The Committee were at first

disposed to doubt her sweeping statement, but when they

heard particularly how she had been treated, they

thought Catharine had good ground for all that

she said. Personal abuse and hard usage,

were the common lot of poor slave girls.

ROBERT

was thirty-five years of age, of a chestnut color, and

well made. His report was similar to that of many

others. He had been provided with plenty of hard

drudgery—hewing of wood and drawing of water, and had

hardly been treated as well as a gentleman would treat a

dumb brute. His feelings, therefore, on leaving

his old master and home, were those of an individual who

had been unjustly in prison for a dozen years and had at

last regained his liberty.

[Page 299]

The civilization, religion, and

customs under which Robert and his companions had

been raised, were, he thought, "very wicked."

Although these travelers were all of the field-hand

order, they were, nevertheless, very promising, and they

anticipated better days in Canada. Good advice was

proffered them on the subject of temperance, industry,

education, etc. Clothing, food and money were also

given them to meet their wants, and they were sent on

their way rejoicing.

_______________

ESCAPED

FROM "A WORTHLESS SOT."

JOHN ATKINSON

John was a prisoner of

hope under James Ray; of Portsmouth, Va.,

whom he declared to be “a worthless sot.” This

character was fully set forth, but the description is

too disgusting for record. John was a dark

mulatto, thirty-one years of age, well-formed and

intelligent. For some years before escaping he had

been in the habit of hiring his time for $120 per annum.

Daily toiling to support his drunken and brutal master,

was a hardship that John felt keenly, but was

compelled to submit to up to the day of his escape.

A part of John's life he had suffered many

abuses from his oppressor, and only a short while before

freeing himself, the auction-block was held up before

his troubled mind. This caused him to take the

first daring step or saying a word to her as to his

intention of fleeing.

John came as a private passenger on one of the

Richmond steamers, and was indebted to the steward of

the boat for his accommodations. Having been

received by the Committee he was cared for and sent on

his journey Canada-ward There he was happy, found

employment and wanted for nothing but his wife and

clothing left in Virginia. On these two points he

wrote several times with considerable feeling.

Some slaves who hired their time in addition to the

payment of their monthly hire, purchased nice clothes

for themselves, which they usually valued highly, so

much so, that after escaping they would not be contented

until they had tried every possible scheme to secure

them. They would wright back continually, either

to their friends in the North or South, hoping thus to

procure them.

Not unfrequently the persons who rendered them

assistance in the South, would be entrusted with all

their effects, with the understanding, that such

valuables would be forwarded to a friend or to a

Committed at thes earliest opportunity. The

Committee strongly protested against fugitives wright or

bump the chairs.

[Page 300]

parties into danger, as all such letters were liable to

be intercepted in order to the discovery of the names of

such as aided the Underground Rail Road. To render

needless this writing to the South the Committee often

submitted to be taxed with demands to rescue clothing as

well as wives, etc., belonging to such as had been

already aided.

The following letters are fair

samples of a large number which came to the Committee

touching the matter of clothing, etc.:

| |

|

ST. CATHARINES,

Sept. 4th. |

DEAR SIR:—I

now embrace this favorable opportunity of writing you a

few lines to inform you that I am quite well and arrived

here safe, and I hope that these few lines may find you

and your family the same. I hope you will

inter-cede for my clothes and as soon as they come

please to send them to me, and if you have not time, get

Dr. Lundy to look out for them, and when

they come he very careful in sending them. I wish

you would copy off this letter and give it to the

Steward, and tell him to give it to Henry Lewy

and tell him to give it to my wife. Brother sends

his love to you and all the family and he is overjoyed

at seeing me arrive safe, he can hardly contain himself;

also he wants to see his wife very much, and says when

she comes he hopes you will send her on as soon as

possible. Jerry Williams' love,

together with all of us. I had a message for Mr.

Lundy, but I forgot it when I was there. No

more at present, but remain your ever grateful and

sincere friend,

JOHN ATKINSON

| |

|

ST. CATHARINES,

C. W., Oct. 5th, 1854 |

MR. WM.

STILL:—Dear Sir—I have learned

of my friend, Richmond Bohm, that my

clothes were in Philadelphia. Will you have the

kindness to see Dr. Lundy and if he has my

clothes in charge, or knows about them, for him to send

them on to me immediately, as I am in great need of

them. I would like to have them put in a small

box, and the overcoat I left at your house to be put in

the box with them, to be sent to the care of my friend,

Hiram Wilson. On receipt of this

letter, I desire you to write a few lines to my wife,

Mary Atkins, in the care of my friend,

Henry Lowey, stating that I am well and

hearty and hoping that she is the same. Please

tell her to remember my love to her mother and her

cousin, Emelin, and her husband, and Thomas

Hunter; also to my father and mother. Please

request her to write to me immediately, for her to be of

good courage, that I love her better than ever. I

would like her to come on as soon as she can, but for

her to write and let me know when she is going to start,

| |

Affectionately Yours, |

JOHN ATKINS.

W. H. ATKINSON, Fugitive, Oct., 1854 |

WILLIAM BUTCHER,

ALIAS

WILLIAM T. MITCHELL.

“HE WAS ABUSEFUL.”

This passenger reported himself from

Massey’s Cross-Roads, near Georgetown, Maryland.

William gave as his reason for being found

destitute, and under the necessity of asking aid, that a

man by the name of William Boyer, who followed

farming, had deprived him of his hard earnings, and also

claimed him as his property; and withal that he had

abused him for

[Page 301]

years, and recently had "threatened to sell" him.

This threat made his yoke too intolerable to be borne.

He here began to think and plan for the future as he

had never done before. Fortunately he was

possessed with more than an average amount of mother

wit, and he soon comprehended the requirements of the

Underground Rail Road. He saw exactly that he must

have resolution and self-dependence, very decided, in

order to gain the victory over Boyer. In

his hour of trial his wife, Phillis, and child,

John Wesley, who were free, caused him

much anxiety; but his reason taught him that it was his

duty to throw off the yoke at all hazards, and he acted

accordingly. Of course he left behind his wife and

child. The interview which the Committee held with

William was quite satisfactory, and he was duly

aided and regularly despatched by the name of William

T. Mitchell. He was about twenty-eight

years of age, of medium size, and of quite a dark hue.

_______________

"WHITE

ENOUGH TO PASS"

JOHN WESLEY

GIBSON represented himself to be not only the

slave, but also the son of William Y. Day, of Taylor’s

Mount, Maryland. The faintest shade of colored

blood was hardly discernible in this passenger. He

relied wholly on his father’s white blood to secure him

freedom. Having resolved to serve no longer as a slave,

he concluded to “hold up his head and put on airs.”

He reached Baltimore safely without being discovered or

suspected of being on the Underground Rail Road, as far

as he was aware of. Here he tried for the first

time to pass for white; the attempt proved a success

beyond his expectation. Indeed he could but wonder

how it was that he had never before hit upon such an

expedient to rid himself of his unhappy lot.

Although a man of only twenty eight years of age, he was

foreman of his master’s farm, But he was not

particularly favored in any way on this account.

His master and father endeavored to hold the reins very

tightly upon him. Not even allowing him the

privilege of visiting around on neighboring plantations.

Perhaps the master thought the family likeness was

rather too discernible. John believed that

on this account all privileges were denied him, and be

resolved to escape. His mother, Harriet,

and sister, Frances, were named as near kin whom

he had left behind. John was quite smart,

and looked none the worse for having so much of his

master’s blood in his veins. The master was alone

to blame for John’s escape, as he passed on his

(the master’s) color.

[Page 302]

One morning about the first of

November, in 1855, the sleepy, slave holding